A.After completing coursework in the Graduate School of Social and Cultural Studies at Kyushu University and withdrawing before the degree was conferred, I worked as a researcher at the Nagasaki Museum of History and Culture. I later joined Siebold University of Nagasaki, now part of the University of Nagasaki, where I currently serve as a professor.My main work at the university focuses on Japanese history. I also leverage our status as a prefectural institution to offer classes on the history and culture of Nagasaki.

A.I am from Sasebo City in Nagasaki Prefecture, a town that developed as a naval port in the Meiji period. Some of my ancestors also served in the navy. With that background, I naturally became interested in naval affairs and, looking further back in time, became fascinated by the Edo‑period coastal defense policies that would go on to become my main research focus.More specifically, I am interested in how Japan’s maritime defense system was maintained during the period commonly referred to as sakoku, or “national isolation.”

A.I am working on two main projects. The first examines how information from overseas reached Japan, how the content and quality differed by route, and how that information influenced the shogunate’s foreign policy. For example, reports on conditions in China—such as the progress of the Taiping Rebellion—brought via Tsushima, Nagasaki, Satsuma, and other channels show both time lags and discrepancies. These factors help illuminate the link between information pathways and policy decisions. The second focuses on Edo‑period Nagasaki. I pay particular attention to the residences maintained there by western Japan daimyo (feudal lords) and explore the possibility that Nagasaki functioned not only as a trading port but also as a political center. While Nagasaki is widely seen as a “trading city,” clarifying its political role may prompt a reappraisal of the Tokugawa shogunate’s foreign policy and regional rule.

A.Shimaya Ichizaemon was a sailor with overseas voyaging experience who transmitted navigation techniques and related knowledge to the Mito branch of the Tokugawa family. This alone shows he was an exceptional captain, combining advanced navigational knowledge with extensive practical experience. Because the inspection of the Ogasawara Islands was undertaken by order of the shogunate and he was entrusted with the mission, it is clear the shogunate placed great trust in him. His ability to organize a large crew, complete the mission, and deliver concrete results also speaks to strong leadership and follow‑through.

A.At the end of Kanbun 9 (1669), a ship carrying mandarin oranges from Kii Province to Edo met with disaster after departing Anoriura. The uninhabited island on which the crew drifted ashore after about 70 days is thought to have been present‑day Hahajima. They then stayed on the island for roughly 50 days and returned via Chichijima, Mukojima, and finally Hachijojima. This incident was reported to the shogunate and prompted recognition that uninhabited islands existed beyond Hachijojima. Several years later, in Enpo 2 (1674), the shogunate’s chief commissioner of finance quietly ordered Suetsugu Heizo, a former Nagasaki magistrate, to verify reports of a “deserted island” (*hito‑nashi shima*) near Hachijojima. The investigation was entrusted to the captain, Shimaya Ichizaemon, and the supercargo (cargo supervisor), Nakao Shoemon. The extant documents do not make clear whether there were additional aims beyond confirming the islands’ existence, or why the expedition was carried out at that particular time.

A.Sources describe the vessel as a shogunal ship built in the Chinese style (*tosen‑zukuri gofune*), modeled on Chinese ships that called at Nagasaki. Records indicate that the first such ship was built in Kanbun 10 (1670), and the second in Kanbun 12 (1672) or Kanbun 13 (1673). The first ship was damaged in Kanbun 13 (1673) off Anoriura in Shima Province (present‑day waters off Mie Prefecture), so the second vessel was used for the Ogasawara inspection. For the first ship, sources survive that even record the hull colors, but details of the second ship are unknown. When the second vessel was built, however, the shogunate ordered that lessons from operating the first ship be applied, so performance improvements were likely made.

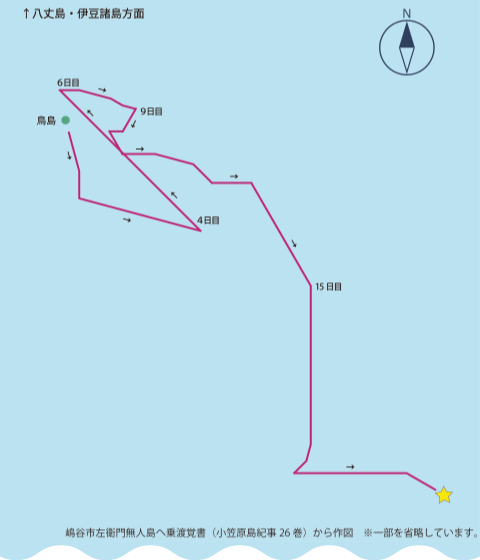

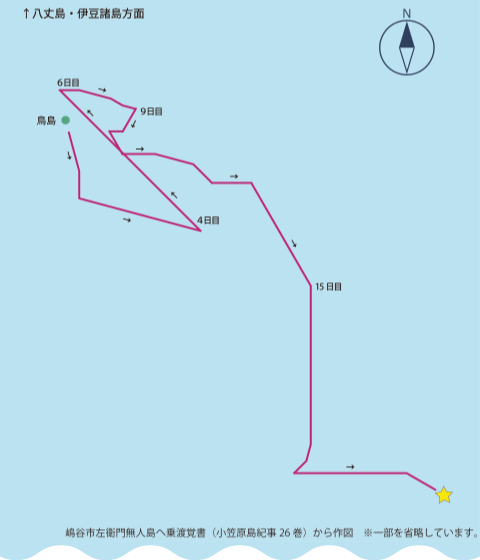

A.In Enpo 2 (1674), Shimaya and his party set sail once, but they apparently returned to port because of bad weather. The following year, on the 5th day of the intercalary fourth month, they departed again from Shimoda. Two days later they reached Hachijojima, and four days after that they passed Aogashima. On the morning of the 11th day of the intercalary fourth month—about a week after departure—they were approximately 380 km from Hachijojima. From there the voyage became extremely difficult as the ship was buffeted by the wind. Although they initially aimed south, they were driven northwest by the wind, then corrected course to the east, and eventually steered southeast again. Several notations indicate changes in heading during the night, suggesting that they adjusted their course by the stars while searching for the silhouette of land. Finally, on the morning of the 29th day of the intercalary fourth month, they sighted land. After sailing roughly 25 ri (about 64 km) east‑southeast, they arrived at the island now known as Chichijima.

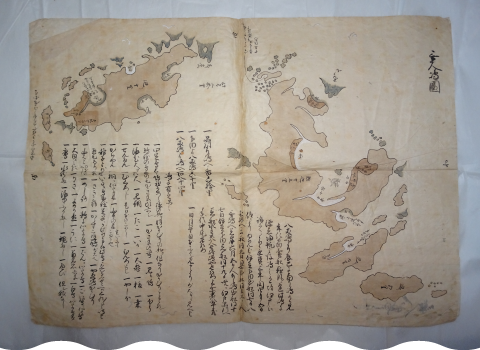

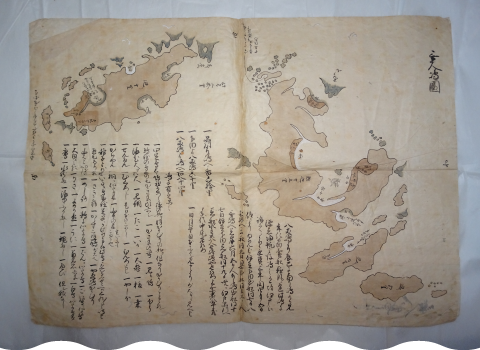

A.From the 1st day of the fifth month onward, the party went ashore. Using prefabricated (knockdown) timbers they had loaded on the ship, they assembled a small boat, sailed around the island, and conducted surveys from the sea as well. They also discovered another large island to the south (Hahajima) and carried out surveys both on land and at sea, including measurements of water depth and observations of the distribution of seaweed. Maps thought to have been produced during Shimaya’s visit record in detail the size of the islands and the depth of the surrounding waters, and they depict the locations of beaches and reefs with striking precision. Surveys were also conducted on the islands’ native plants, animals, and minerals; some specimens were collected and brought back to the mainland.

A.A man named Ogasawara Sadato, who claimed to be a descendant of Ogasawara Sadayori, petitioned the shogunate for permission to travel to the islands so he could carry on the exploits of his supposed ancestor, who was credited with discovering the uninhabited islands. Although his request was initially granted, it later came to light that his claims were fabricated, and he was punished with permanent banishment. Because of this, historians today regard Ogasawara Sadayori as a fictitious figure, and we know that he had no connection to Shimaya Ichizaemon, who actually conducted the surveys of the uninhabited islands. As evidence to support his claims, Sadato submitted an anonymous work titled Tatsumi Mujintoki (“Record of the Uninhabited Island to the Southeast”), which also included a passage about the naming of “Ogasawara Island.” Even though the text was later revealed to be fabricated, the account spread, and names such as “Ogasawara Island” became established and remain in use today.

A.The shogunate decided to dispatch the second Chinese‑style shogunal ship to the “deserted island” and—despite his having health problems—again appointed Shimaya Ichizaemon as captain. This attests to the shogunate’s deep trust in him. Given that this difficult voyage ended in success, we can regard Shimaya’s extensive navigational experience, his excellent seamanship, and the sailors who supported him not merely as factors that enabled the successful inspection of the “deserted island” (the Ogasawara Islands), but as the culmination of Japan’s navigational techniques, shipbuilding technology, and personnel management at the time. In that sense, this voyage is also a concrete example that demonstrates Nagasaki’s strengths in both shipbuilding and human resources. From another perspective, the greatest significance for the shogunate lay in confirming the existence of previously unknown islands south of Hachijojima and, through the unfamiliar objects that Shimaya’s party brought back, gaining new knowledge of nature, geography, and local products.

A.The long neglect of Shimaya’s inspection can be attributed largely to Edo‑period geopolitical priorities and the way information was controlled. At that time, the Tokugawa shogunate’s foreign policy focused on limited relationships with Joseon Korea, Qing China, the Ryukyu Kingdom, and the Netherlands, emphasizing the collection and management of foreign information through hubs such as Tsushima, Nagasaki, and Satsuma. In that policy environment, the southern seas beyond the Kuroshio Current—especially the Pacific island regions—were hard to navigate and offered little economic or military advantage. They therefore did not develop into areas where the shogunate envisaged sustained governance or use. Moreover, geographic information in the Edo period was strictly controlled by the shogunate and rarely released to the public. This information‑control regime meant that knowledge of Shimaya’s inspection voyage itself did not easily take hold as part of a broader historical memory. That said, in Nagasaki his achievements were in fact passed down. In Nagasaki Senminden (“Biographies of the Former Worthies of Nagasaki”), compiled in the early eighteenth century and describing the lives of 147 individuals connected with Nagasaki who distinguished themselves in Confucian scholarship, astronomy, calendar science, medicine, and other fields, Shimaya Ichizaemon is also included. In other words, Nagasaki did preserve the memory of his accomplishments.

A.I feel a strong sense of fulfillment when, in the process of reading and interpreting historical sources, I encounter facts that were previously unknown. Individual documents contain only fragmentary pieces of information, but when those fragments begin to connect and the dots turn into lines, a coherent historical picture gradually comes into view. When that process leads to new interpretations or perspectives, I feel the true excitement of historical research. To give an example related to my current work: during a source survey at Honkoji Temple in Shimabara City, Nagasaki Prefecture, I happened by chance to photograph a “Map of the Uninhabited Island.” When I later checked which island it depicted, I discovered that it was actually a map of the Ogasawara Islands. I then realized that its content differed in important ways from the maps that were already known and that it was previously unintroduced. As a researcher, these moments of uncovering knowledge are thrilling.

A.The Ogasawara Islands, which belong to the Tokyo Metropolis, may be best known as a World Natural Heritage site, but they are also a place of immense historical interest. For example, historical figures whose names most people have heard at least once—such as Commodore Perry and John Manjiro—visited the islands. Those interested in late Edo–period history may also know that the warship *Kanrin‑maru* called at Ogasawara. I would like to invite you to visit the Ogasawara Islands and experience the history that lives on there. I hope that, in addition to enjoying the islands’ rich natural environment, you will also take a moment to turn your attention to this remarkable history.