A.The first time I went there from Naha, and the second time from Ogasawara. Both times, I spent two nights on the ship and one or two days on the island. The whole of Okinotorishima Islands measures 1.75 km from north to south and 4.5 km from east to west, but most of it's below sea level at high tide, and only two parts of it are islands under international law. These are the islets Kita-Kojima and Higashi-Kojima. They're both about big enough for someone to lie down on. The islands are surrounded by concrete seawalls, and we landed on those.

A.We were only there for a day so we couldn't do any very thorough work, but we did investigate each island's environment. We also looked at how the corals around them live. The research also involved snorkeling, scuba diving, and underwater photography. The edge (reef crest) of Okinotorishima Islands is dry land at low tide. In the interior (the lagoon), the water is only about 5 m even in the deepest places, so you can snorkel.

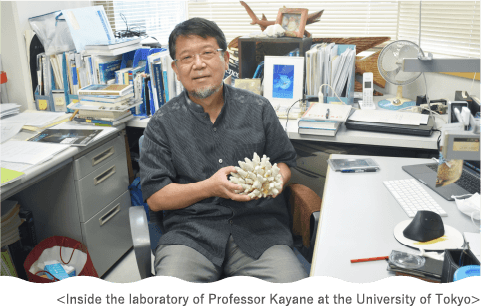

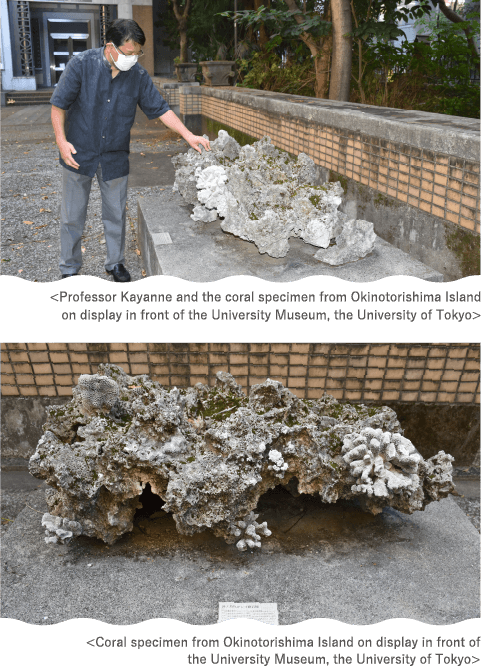

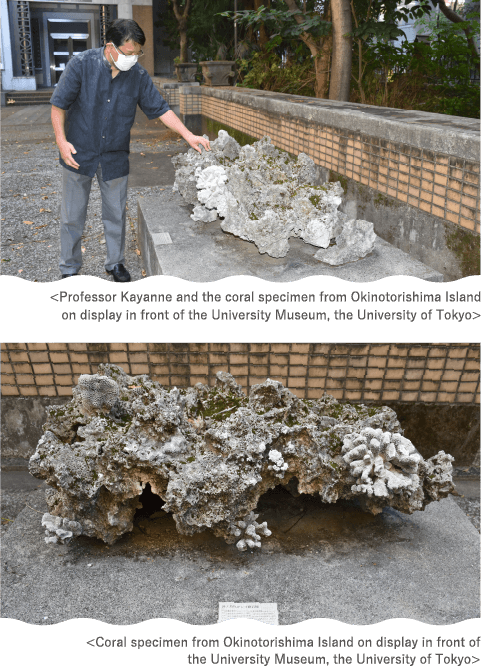

A.Some coral specimens from Okinotorishima Islands from have been donated to the University Museum at the University of Tokyo. They weren't brought back by me, but collected by the Fisheries Agency and the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism (or MLIT)'s Keihin River Office for a preservation project. There's also some reef rock on public display. Rocks collected from around the island were studied to test their engineering properties by measuring their hardness and so on. They were subsequently donated to the University of Tokyo, and can currently be seen at the museum entrance. You can still see the coral skeletons in them.

A.Like the first visit to Okinotorishima Islands, the second one was also for a preservation project by MLIT. The main focus was to observe the situation on the island rather than conduct studies. Things don't appear to be changing much, but the Fisheries Agency is working on developing technology to cultivate Okinotorishima Islands coral seeds, and according to its research, bleaching and other factors have been causing a dramatic decline in the corals there since around 2014. In that sense, I think Okinotorishima Islands is in undergoing major change.

A.As I mentioned just now, one is the Fisheries Agency's work toward developing technology to cultivate Okinotorishima Islands coral seeds. Most research is looking into so-called "asexual reproduction," in which once the corals have multiplied, some of them are broken off, transplanted, and grown. On the other hand, the Fisheries Agency is working on "sexual reproduction," in which the corals are increased by hatching them from eggs. The aim is to help the corals increase and grow in the harsh environment around Okinotorishima Islands. I've been involved as a member of the committee since this seedling production technology was first developed back in 2006, and am currently the chair. In this role, I'm involved in evaluating the project.

Another area of work is technology to preserve the island. A project is underway to investigate not just how to protect the existing island with seawalls, but also how to preserve it more effectively, and whether submersion of the island can be prevented by piling up coral fragments. The island wouldn't be recognized as an island under international law even if we hardened it and built it up with concrete, so we'll need to utilize the natural mechanism whereby islands are formed by the buildup of a coral foundation. To that end, we're pursuing research using a new ecological engineering technology.

We're also building port facilities to enable ships working around Okinotorishima Islands to moor and berth smoothly, and are currently discussing various environmental preservation measures that this could make possible.

In addition, the Tokyo Metropolitan Government is continuing to advertise Okinotorishima Islands to the aquaculture industry, Tokyoites, and the rest of the nation.

To sum up, the Fisheries Agency, MLIT, and Tokyo Metropolitan Government are all working to preserve Okinotorishima Islands.

A.Yes, that's right. That said though, the purpose varies between organizations, with the Fisheries Agency aiming to increase the corals and MLIT aiming to preserve and utilize the island. The Okinotorishima Islands Study Group was launched in 2006 to investigate going beyond sectoral boundaries and preserving Okinotorishima Islands comprehensively. With that, a forum was created for people involved to exchange information. Currently, more than 200 people from universities, research institutes, government agencies, foundations, and the private sector are involved, working as members of the UTokyo Ocean Alliance Okinotorishima and Small Island Countries Study Group. The goal is to protect the island as well as increasing the corals, so we'll all work together—regardless of boundaries between government agencies and sectors—to develop environmental preservation technology, and construct a grand design to apply to atoll islands.

A.Predictions say the sea level is going to rise by up to a meter by the middle of this century. Okinotorishima Island's current height is just a few dozen centimeters, so it's extremely likely that the rising sea level will swallow it up. To avoid the submersion crisis, we're growing coral then piling up broken-off fragments to preserve the island naturally. The idea is that we're helping the mechanism by which living things drive the formation of atoll islands.

A.Right. Barasu Island around Iriomote Island was formed by the accumulation of coral debris. I want to investigate how it became an island, and use the knowledge gained to help preserve Okinotorishima Islands. It's also important to know what mechanisms lie behind atoll islands' topography. I want to further my own research based on studies of them, so we can use coral power to prevent the atoll islands from getting submerged.

A.Yes, it is. It's currently rising by about 3 mm a year. Global warming is causing water to thermally expand and glaciers to melt, and these in turn are causing the sea level to rise. According to a report by the IPCC, the sea level has already risen by 0.2 m due to melting ice in places like the Antarctic and Greenland, and it's predicted to rise by another 0.1 to 0.8 m by the end of the century. Besides that, global warming is increasing the water temperature. Because of this, large-scale coral bleaching is now a frequent occurrence around Okinotorishima Islands as well.

We need to put even more effort into increasing the corals so they can withstand the rising sea level and water temperature.

A.Building up the island artificially won't solve the problem: we need to use nature's mechanisms to protect it. We're going to form the island by encouraging coral growth and building up broken-off fragments around it. Nothing like that's ever been done before, so I want to work on it as a new ecological engineering eco-technology. Our program's goal is to take this technology developed on Okinotorishima Islands and apply it to atoll islands in Tuvalu, Kiribati, the Maldives, and other places similarly at risk of submersion due to the rising sea level. That way, it'll play a leading role in the Pacific Ocean's environmental security.