A. The Yamashina Institute for Ornithology specializes in the study of birds. The predecessor of the institute is the laboratory museum privately built by Dr. Yamashina Yoshimaro within his residence in 1932. As more and more researchers were beginning to make use of the museum, the Ministry of Education authorized its development into the Yamashina Institute for Ornithology in 1942. In 1984, the institute moved to its current location in Abiko, and in 1986, His Imperial Highness Prince Akishino became the president of the institute. In 2012, the institute transitioned into a public interest incorporated foundation. As of 2024, the institute has 23 members, 14 of whom are researchers and specialists.

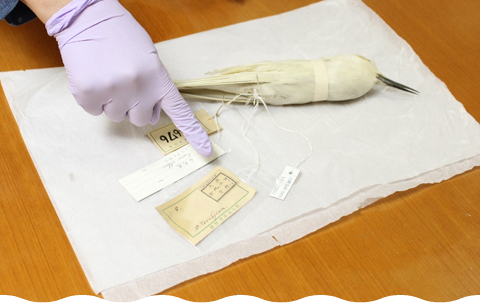

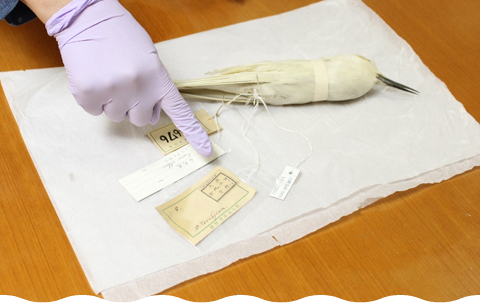

〈 Type specimen of the Okinawa Rail Hypotaenidia okinawae owned by the Yamashina Institute for Ornithology 〉

〈 Type specimen of the Okinawa Rail Hypotaenidia okinawae owned by the Yamashina Institute for Ornithology 〉

〈 Model of Torishima Island, the Izu Islands, where Short-tailed Albatrosses breed 〉

〈 Model of Torishima Island, the Izu Islands, where Short-tailed Albatrosses breed 〉

The Yamashina Institute for Ornithology conducts research to aid in the preservation of rare species such as the endangered Okinawa Rail Hypotaenidia okinawae and Short-tailed Albatross Phoebastria albatrus. The Okinawa rail was described as a new species by Dr. Yamashina and Mano Toru, a member of the institute, after researchers succeeded in capturing in 1981. The Okinawa Rails are distributed in the northern Okinawa Island. However, its population has been greatly reduced due to the northward invasion of mongooses, a predator. While current preservation efforts are enabling the Okinawa Rail to repopulate and inhabit a larger area, the species still faces many dangers, including traffic accidents. Preservation efforts for the Short-tailed Albatross began in 1991, and have increased the population size by installing decoys (life-size models of albatrosses) on Torishima Island, the Izu Islands, where there was only one breeding site, and by establishing other breeding sites on the island. However, as Torishima Island is a volcanic island, there is the danger of eruption, so efforts are also being made to establish a new breeding colony on Mukojima Island, the Ogasawara Islands.

The Yamashina Institute for Ornithology has also been commissioned by the Ministry of the Environment to conduct “bird banding” to study bird’s migration, lifespans and so on by attaching leg bands or other identifiable devices. In addition to the surveys conducted by members of the institute in various locations, approximately 400 volunteers across the country conduct the same surveys. Since 1961, such 6.1 million bird banding data have been collected. In addition, both specimens and ornithological books held by the Yamashina Institute for Ornithology are fundamental and essential materials for the study of birds, including especially precious materials, such as specimens of extinct birds, or natural history books published in the 19th century. Since the establishment of Dr. Yamashina’s laboratory museum, the institute has been continuously collected ornithological materials, and thus has held 80,000 specimens, 70,000 books and archival documents, and 20,000 tissue and DNA samples, today. The Yamashina Institute for Ornithology also publishes a scientific journal and a newsletter to announce the institute’s activities.

〈 Type specimen of the Okinawa Rail Hypotaenidia okinawae owned by the Yamashina Institute for Ornithology 〉

〈 Type specimen of the Okinawa Rail Hypotaenidia okinawae owned by the Yamashina Institute for Ornithology 〉

〈 Model of Torishima Island, the Izu Islands, where Short-tailed Albatrosses breed 〉

〈 Model of Torishima Island, the Izu Islands, where Short-tailed Albatrosses breed 〉

A. After graduating from university in 1996, I was hired to work in the Public Relations of Yamashina Institute for Ornithology. In 2004, I was transferred to the Collection Room, where I was placed in charge of collecting and managing specimens. There, I began learning from the ground up about what is specimens and how to manage them. Many of the specimens at the Yamashina Institute for Ornithology are very old. Some of them were collected by prominent ornithologists, and the other are precious specimens of extinct species, so I became interested in the backgrounds of the specimens. In 2013, as a student with a full-time job, I enrolled in a doctoral program provided by the Graduate School of Agriculture at Hokkaido University to study the history of specimens under Dr. Kato Masaru. I received a PhD from the Graduate School of Agriculture, Hokkaido University in 2022.

A. I have always loved animals, and I entered the Department of Animal Science, Nihon University. I studied on the hormones of Japanese Bush Warblers Cettia diphone for my graduation thesis, and that is what got me interested in wild birds. In study of the hormonal changes during breeding season of the Japanese Bush Warbler, it was necessary to capture the same individual numerous times in order to collect blood samples. However, if captured once, wild birds remember the trap and the voices to lure them in, so I was completely unable to re-capture them for the second and third rounds of surveys. When I was at a loss for what to do in capturing, I could luckily encounter a researcher who was studying the sounds of the Japanese bush warbler and working in the Yamashina Institute for Ornithology. He taught me that when the warblers sing the initial “hoo-” portion of their “hoo-hokekyo” notes in a high-pitched tone, it means that they are relaxed, and when in a low-pitched tone that they are on alert. I was deeply impressed to learn that there are rules to song of the Japanese bush warbler. I feel that the experience gave me an opportunity to understand the depth and interest of observing and studying wild birds.

A. I was placed in charge of collecting and managing specimens, and I was primarily responsible for registration of specimens and materials. I continue to do this even now. There are laws and treaties that cover the transfer of bird remains, and it is necessary to be aware of the regulations when accepting rare species or exchanging specimens with overseas museums, so I have to remain up-to-date on these laws and treaties because they are constantly being revised. In recent years, we have had to assume that the birds have died of avian influenza, and in some cases, we have had to recommend that they be sent to a laboratory before we receive them. Apart from this, I had an opportunity to read a paper on specimen management conducted at a museum of the U.S., and I inspected the museum of the U.S. to learn the management. At the time, the Yamashina Institute for Ornithology was about to be in transition from paper registers to a digital database, so it was very educational to see the systematic specimen management at the museum in the U.S. After a period of trial and error by the staff members involved, we now have a system in place for the entire process, from accepting bird remains through to dissection, tissue sample collection, specimen preparation, storage, and publication in the specimen database. I believe that this system is something that we can be proud of, even when compared to other museums and institutions in Japan.

〈 In a conference room at the Yamashina Institute for Ornithology 〉

〈 In a conference room at the Yamashina Institute for Ornithology 〉

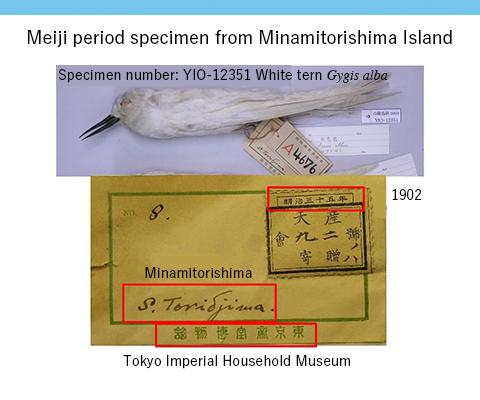

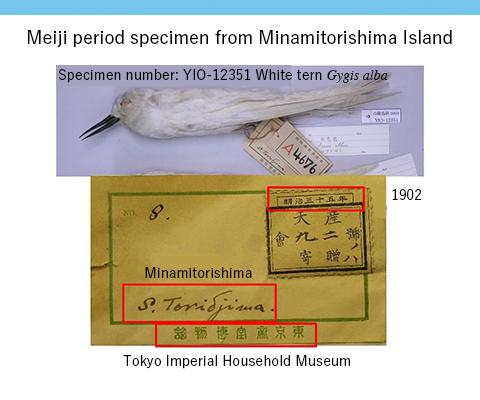

A. When I was a graduate school student, I conducted research on the history of bird specimens that had been held by the Tokyo Imperial Household Museum (now known as the Tokyo National Museum but hereinafter referred to as the Imperial Household Museum). The Yamashina Institute for Ornithology has about 3,300 specimens that used to be held by the Imperial Household Museum, including specimens of extinct species, type specimens used as evidence for the description of new species, and various other specimens of great scientific importance. However, the origins of many of these specimens, such as who collected them and how, was unknown. In method of my research, I find a specimen group suspected to be derived from the same origin base on specimen registers and on specimen labels, and then investigate literature and materials involving in the characteristics of the specimen group. I discovered that, according to the specimen registers of the Imperial Household Museum, the specimens from Minamitorishima Island were intensively donated by several donors in 1902 and 1903. While I was looking into the events of this period, Dr. Kato of Hokkaido University told me that the book “Albatrosses and the Expansion of ‘Imperial’ Japan” (2012, Akashi Shoten), written by Dr. Hiraoka Akitoshi, provides a detailed account of the 1902 Minamitorishima Island Incident. In July 1902, the Japanese government was aware that an American sailing ship was enroute to Minamitorishima Island with the goal of taking control of the island and collecting guano (the accumulated excrement of seabirds, etc. used as a fertilizer resource). Then, the government dispatched a warship to explain that Minamitorishima Island was Japanese territory, and urged the ship to return to the U.S. This became known as the Minamitorishima Island Incident. At this time, the crew members of the American sailing ship were permitted by the Japanese Navy to stay for a week. William Alanson Bryan (affiliated with the Bishop Museum in Hawaii), who was aboard the ship, conducted a survey of the island’s flora and fauna during his stay, and published a report the following year in 1903. This report is now a valuable reference on the flora and fauna of Minamitorishima Island during the Meiji period (1868-1912).

〈 A specimen from Minamitorishima Island formerly held by the Imperial Household Museum 〉

〈 A specimen from Minamitorishima Island formerly held by the Imperial Household Museum 〉

A. The specimens from Minamitorishima Island were donated to the Imperial Household Museum in 1902 and 1903. The National Museum of Nature and Science (known at the time as Tokyo Museum) was completely destroyed in the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923, and all of the specimens were lost, so most of the natural history specimens at the Imperial Household Museum were transferred to the National Museum of Nature and Science Some of the natural history specimens were also transferred to the Gakushuin School Corporation. The specimens at the Yamashina Institute for Ornithology that were formerly held by the Imperial Household Museum were transferred to the institute from Gakushuin after World War II. According to the number of specimen registered, the Imperial Household Museum had held as many as 5,000 bird specimens, approximately 4,000 of which had been considered to survive the Great Kanto Earthquake. The Yamashina Institute for Ornithology stores 3,300 specimens, roughly 80% of the specimens which survived the Great Kanto Earthquake, which means that the majority of the Imperial Household Museum’s bird specimens were still in existence.

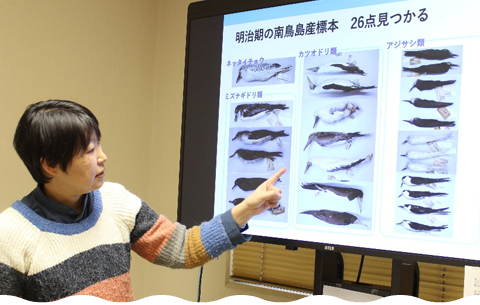

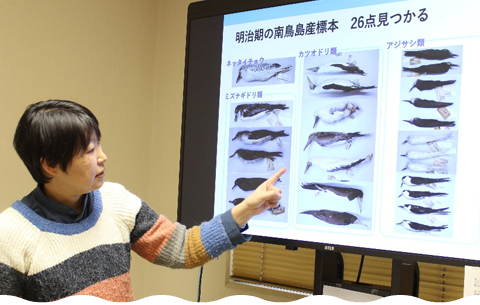

A. We have confirmed that there are 111 bird specimens from Minamitorishima Island in Japan. The Yamashina Institute for Ornithology has 26 specimens formerly held by the Imperial Household Museum. There is one specimen that was collected by William Alanson Bryan and that came from Bishop Museum. Three specimens related to the Minamitorishima Island Incident came from Tokyo Imperial University. There are 12 specimens collected around 1910 that came from the collection of ornithologist Matsudaira Yorinari. Another 18 specimens were collected by Dr. Kuroda Nagahisa, a former director general of the institute, while surveying Minamitorishima Island in 1952 after WWII. One specimen was collected by Mr. Fujisawa Itaru, an employee of the Japan Meteorological Agency, and another specimen was purchased from Shimadzu Corporation. Outside of Japan, the Bishop Museum holds 44 specimens brought back from the Minamitorishima Island Incident by William Alanson Bryan. Combining those in Japan and overseas, we have confirmed a total of 155 bird specimens from Minamitorishima Island to extant.

〈 Dr. Kobayashi explaining bird specimens from Minamitorishima Island 〉

〈 Dr. Kobayashi explaining bird specimens from Minamitorishima Island 〉

A. Of the 11 species for which we have specimens from Minamitorishima Island that were formerly held by the Imperial Household Museum, eight used to breed on the island. Surveys in recent years have confirmed that three of these species still breed there, which means that five species no longer breed on Minamitorishima Island.

In 1902, William Alanson Bryan collected the specimens of 11 species transferred to the Imperial Household Museum in later years; in this year, he confirmed that eight of those species bred on the island through his surveys. However, Kuroda Nagahisa’s postwar survey in 1952 confirmed that only two species bred there: Brown Noddies Anous stolidus and Sooty Terns Sterna fuscata. This was because the island environment had severely deteriorated due to overhunting during the Meiji period and the fact that it was used as a major military base during World War II. Later, surveys conducted in 1992 and 1993 by Mr. Kawahara Kyoichi, an employee of the Japan Meteorological Agency, confirmed that Red-tailed Tropicbirds Phaethon rubricauda were also breeding on the island, in addition to the Brown Noddies and Sooty Terns. Dr. Kawakami Kazuto, a researcher of the Forestry and Forest Products Research Institute, confirmed in his 2007 survey that Brown Noddies, Sooty Terns, and Red-tailed Tropicbird all bred on the island, and he reported that Laysan Albatrosses Phoebastria immutabilis, of which no specimen is included in the above 11 species, also nested there. We expect that the number of bird species that breed on the island will increase in the future.

〈 Observation or breeding records of the 11 species on Minamitorishima Island on or after the dates when the specimens of those species formerly held by the Imperial Household Museum were collected from the Island. 〉

〈 Observation or breeding records of the 11 species on Minamitorishima Island on or after the dates when the specimens of those species formerly held by the Imperial Household Museum were collected from the Island. 〉

A. I really enjoy the process of researching to uncover their histories. I gather a lot of information by looking back through ledgers, specimen labels, as well as other materials and literature. The information is all interrelated and ultimately develops into a story, and the moment when all of it connects together is very exciting. Conversely, the hardest part is writing and publishing the stories of their histories as research papers. Scientific research is usually conducted by first formulating a hypothesis and then verifying it through experiments and other tests. In my research, however, I first gather information, which I then use to piece together the story of a specimen’s history. This makes it hard to write papers in the typical scientific format. It usually takes me a long time to publish each paper, so I want to try hard to keep getting better at it in the future.

A. We examine its plumage and measurements of the head, wings, tail feathers, and legs, and compare those of known species.

A. Every specimen has its unique background due to the collector. Of the specimens held by the Yamashina Institute for Ornithology, there are so old specimens collected in the 19th century, of which some species have already gone extinct. Uncovering the backgrounds of specimens and restoring information at the time of collection improves the scientific value of them, and then are contributable for the field of natural science. Before I began studying the backgrounds of specimens from Minamitorishima Island collected during the Meiji period, I had pictured Minamitorishima Island as an isolated island out in the middle of the ocean with hardly any resources and only visited by a limited number of birds. However, contrary to how I imagined it, Minamitorishima Island during the Meiji period seemed to have been a resource-rich island inhabited by a wide variety of seabirds. Our study uncovered that the seabird specimens collected on Minamitorishima Island during the Meiji period are still extant. And these specimens are evidence that, during the Meiji period, Minamitorishima Island was in fact a resource-rich island inhabited by a wide variety of seabirds. I believe that is the major achievement of this study.

〈 Specimen of a White Tern from Minamitorishima Island formerly held by the Imperial Household Museum

〈 Specimen of a White Tern from Minamitorishima Island formerly held by the Imperial Household MuseumA. While 11 species of seabirds bred on Minamitorishima Island during the Meiji period, through overhunting and environmental destruction during WWII, the number of seabird species breeding on the island fell to only two according to postwar surveys. Over the period from the end of WWII up to 2007, three species were confirmed to breed on the island, and one species was confirmed to nest. The increase in the seabird breeding species let us expect that former breeding species have gradually recovered. Minamitorishima Island was the only island in Japan where tropical seabirds such as White Terns and Christmas Shearwaters Puffinus nativitatis used to breed. I hope that regular surveys of the birds on Minamitorishima Island will be conducted in the future, and that these surveys will provide the residents of Tokyo and Japan as a whole with opportunities to learn more about the birds of Minamitorishima Island. A case of the Sort-tailed Albatrosses are also symbolic. It was driven to the brink of extinction through the overharvesting of seabird feathers during the Meiji period. The Yamashina Institute for Ornithology has been working to conserve the albatrosses since 1991. Although the albatrosses were once thought to be extinct, conservation efforts for this species have been successful, and the population has now risen back up to 7,900 birds. They, however, remain endangered. Although staffs of the institute continue conservation activities every year on Tori-shima Island, the Izu Islands, and Mukojima Island, the Ogasawara Islands, which are both breeding sites for the albatrosses, it is difficult to cover the costs as there are no regular boats that go to either of these uninhabited islands. We would be grateful for any support you could provide in our efforts to help the albatrosses shed their status as an endangered species.